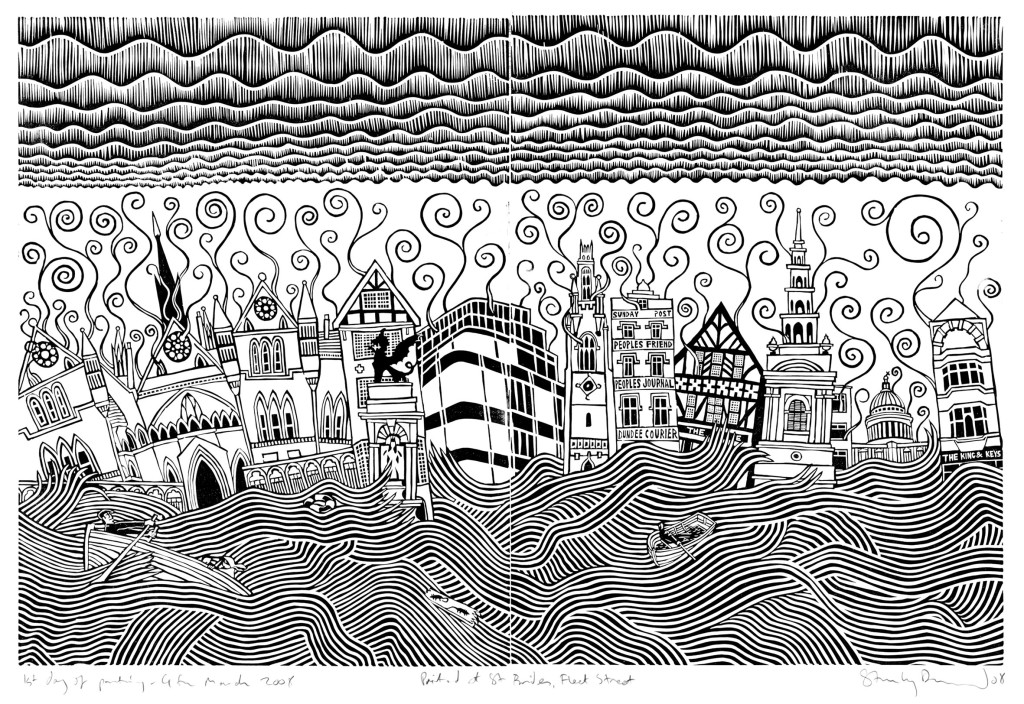

There are some forgotten and/or overlooked prints of Fleet Street Apocalypse for sale at the very place where they were printed, ten years ago. St Bride’s Printing Library is the vendor and all proceeds go to them. Click HERE to go and have a look.

By the way, when they describe it as a ‘facsimile’ they just mean that it’s a print, made directly from the giant linocut that I carved. Maybe facsimile is some archaic printing term that means just that. I dunno.